Summer, 2024

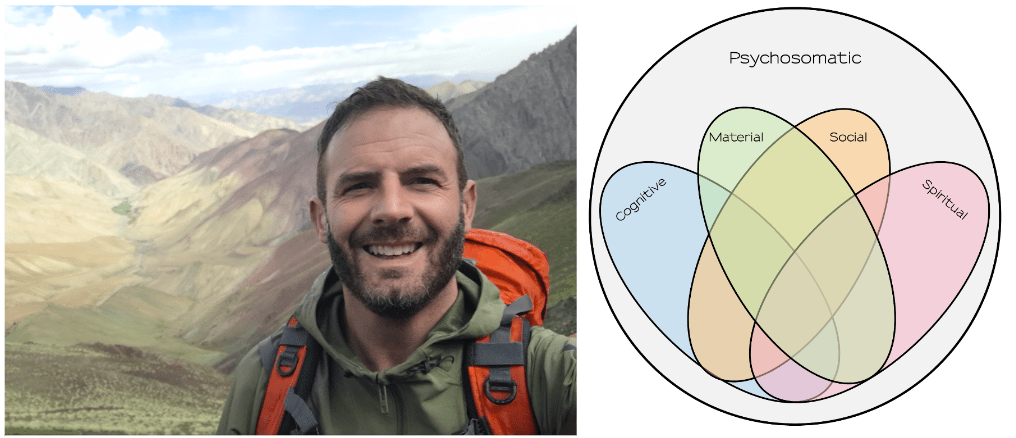

Across the summer holiday, HT teacher, Jon Rees, took an extended trip through Ladakh, in Northern India. As part of a series exploring Human Technologies, Jon relates his insights- focusing this week on the enveloping psychosomatic lens.

(l)The view from halfway up the valley to the Stok-La Pass from Rumbak, which can be located through the bright green splash of cultivated valley floor; (r) The HT Venn Diagram

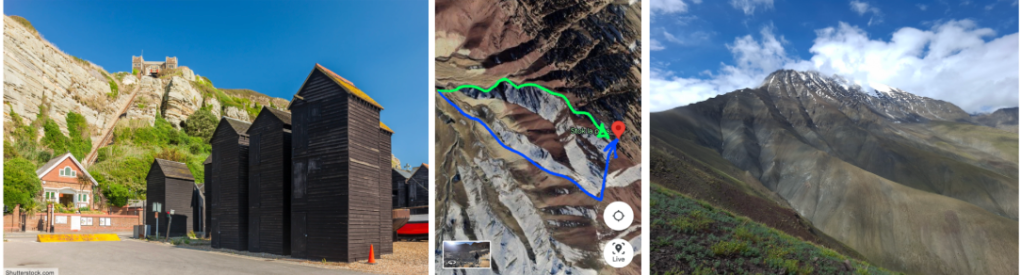

I came to the realisation that I was stuck. Perched high above Rock-a-Nore Road, and clinging on to the Hastings Cliffs that rose up from the dark, wooden fishermen’s smoke shacks below, my legs had locked up and were quivering, my hands were clammy and I had a tight knot in my stomach as adrenaline coursed around my system.

I was probably 7yrs old and my friend, Chris’ mum, had taken a group of us out for a day trip to Hastings, Kent. We had stopped for an ice cream after the cinema and then we had the freedom to go clambering up the rocky cliff face. Except, I realised, I had gone too far, probably showing off and now found myself trapped half way up towards Hastings Castle, staring at the road below and the faces of the pedestrians who all seemed to be mockingly gazing up, and none of whom were offering help.

Places that I have been psychologically and physically stuck: (l) the Hastings Cliffs up to the Castle above the fishing huts when I was seven or eight; (c) the path up from Rumbak towards Stok, via the Stok-La Pass (4900m). The path in blue which I took, and in green, where I should have gone. (r) Stok Kangri (6153,) can be seen rising up along the ridgeline connected to Stok-La Pass.

It was a memory of a moment of physical and psychological duress, a curious deja vu that I came back to almost 35yrs later as I clung onto the side of a bank of shale in Ladakh this summer. So close, just 70m or so, below the top of the 5,000m ridgeline adjoining the Stok-La Pass. Despite taking precautions like Googling and screenshotting the satellite contours, and after assessing what I thought to be the easiest route up the unmarked trail, I had opted for a dog-leg that seemed to follow an easier gradient and that would take me away from the formidable ridge-line ahead which appeared to me like the jagged silhouette of a giant bread knife.

Not sure the photo does this justice, but staring up from the valley floor, I didn’t fancy the route that lay ahead at all. My inclination towards the gentler looking dog-leg off to the right I spied on the Google Satellite image was reinforced through coming-upon rock cairns signifying a used trail ahead.

The purpose of HT, and this article, is to get students to think about the way in which they can regulate their lives through adopting some physical and mental technologies to lead more purposeful, fulfilled lives. I hope to share through some of the lessons I learned along my trip, how I was able to reflect upon one particularly vivid experience that led to a significant shift in my perspective on life. So, as I read this article together with my Y11 group, I will ask them a series of questions so that their own reflections on life can emerge…

Eagle-eyed HT fans might have noticed the updated HT Venn Diagram to include the overarching lens re-labelled from “Somatic” to “Psychosomatic”; what prompted Toby Newton to initiate this change was the clear awareness that not only do we experience and interpret the rest of the other HT circles: Material-Spiritual-Social-Cognitive through our bodies, but also our minds. We are born with our DNA, biograms, genetic dispositions, but for the most part we can’t (yet?) augment our physical and psychological selves.

Back to Ladakh: other precautions I took were researching the route through conversation with a local tour guide, as well as purchasing a Trek Ladakh book with maps of the area, but not, alas, of this exact route. The tour guide confidently suggested that as this was a well-used path, populated by herders driving their flocks, as well as hikers, I could just ask for directions. Actually, there were very few hikers, as I set out for the top early at around 5:30 am, and unlike previous preparatory hikes in the Balkans, and along some of Hong Kong’s 4 main trails across the previous year, there were no handy signposts along the way.

I had followed what appeared to be a used trail from a distance, and, indeed it was; yet, as I put my full weight gingerly down on the loose top rocks and found my foot slide back down the mountain, I quickly ascertained that this was a path for the surefooted blue sheep and mountain goats that could nimbly traverse the slightest edges with their incredible agility and uncanny sense of balance, and not one for an 80kg+ human being. And, as luck would have it, it also started to hail, so, I dug on to the mountainside with my fingernails and spent some time regretting my choices.

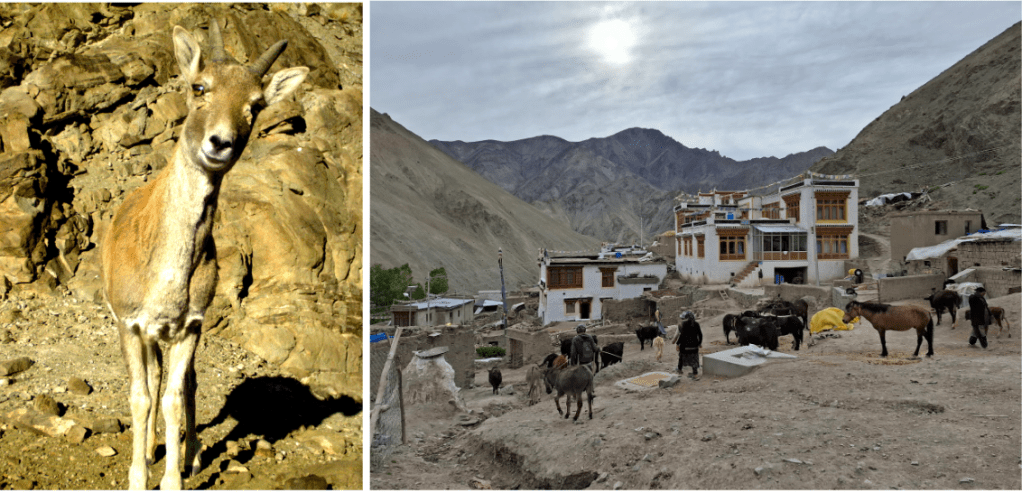

(l) Photo c/o The Snow Leopard Conservancy: The Stok-La Pass presents no problems for this urial, or his blue sheep brethren; (r) a tranquil pastoral scene as the villagers of Rumbak brought their animals down off the hills to the shelter of their pens

In short, the main advice here is not to hike on your own, especially in an area in which you are not familiar. I’m an experienced hiker, and all the way up to the top of the Pass, I could see human habitation back down the valley to Rumbak where I set out. Therefore, I reassured myself that I could be “sure” I was going to get back down if needed. But a twisted ankle, or broken limb could have been really bad that many hours away from help.

I wondered, too, what had caused the decision to embark upon this physical challenge anyhow? What compels us as human beings to pursue these physical goals? I think it is to “know thyself” as the universal maxim across religions speaks to. We want to know our limits, and show a “growth mindset”, as psychologist Carol Dweck would say, as referred to by Natalie Bailey in her Weekly Bulletin article last week.

Perhaps there are also certain psychological underpinnings that compel us to the need to achieve, to be commended, some remnant of childhood, that is, intractably, not simply a legacy of who we were, but who we are today. The Russian Dolls HT metaphor is a simple, but effective way to think about our continued psychological development.

The HT Russian Dolls

As I soon turn 43yrs, and am aghast to find myself in middle-age, I have come to hear more frequently my body’s signs as my metabolism slows down and I notice, for example, my speed diminished in football (not that I had much to begin with).

Yet, my stamina remains strong, and I believe it was the foundation of cross country runs and football undertaken in my youth that have allowed me the platform for enjoying plenty of physical exercise now. Knowing this, I want to engage in physical challenges today while my body still says, “Yes,” rather than wait too long and regret the chances that might have slipped by…

One message for the young students reading this is to really treat your body with respect. You only get one, and, so the adage goes, if your body was a Ferrari you’d garage it, and polish and tune it regularly so that you could enjoy the maximum performance.

And time spent doing physical exercise unlocks many positive benefits for our bodies and mental wellbeing. Check out this short video from Insider Tech:

Back on the mountainside…From this vantage point, with my cheek pressed against the rock, I took some deep breaths to calm my nerves and assessed my options., I turned my head to the left to see the harder rock surface so temptingly close, just another 20m away, and shuffled my foot forward to gauge the resistance. Bad move. Any time I adjusted my body more front-on to the mountainside and attempted to manoeuvre across, the loose rock would abruptly shift beneath my foot and send me jolting another few centimetres down, watching small rocks and pebbles cascade to the bottom of the sharp climb.

So, I gripped the shale and spread myself out starfish-style to try to spread my body weight over a large enough area to prevent me sliding all the way back down to the bottom of the section- about 60 feet below- and thought about what to do next.I had a decision to make: to struggle upwards was impossible, so I could either a) gamble on edging further forward and risk sliding down the bank; b) have a little cry (I really did give this some consideration), or, c) head back the way I had clambered, and evaluate from a safer position.

The rocks around me were so small, the consequence of hundreds of thousands of years of erosion caused by exposure to the fierce winds and freezing winters, so, I felt no great worry about sliding back and creating an avalanche where big boulders would be dislodged following me down, but I did feel that the mental and physical defeat of that moment could just spell the end of the hike and a sorry return to my homestay at Rumbak.

I took some more deep breaths, breathing in through my nose and then slowly out through my mouth as I had used this 4-1-7 breathing technique learned from cognitive neuroscientist, Andrew Hubermans, before to calm myself before an important football match, or whenever I might have to speak in public, or suchlike. You breathe in through your nose, slowly and deeply for 4 seconds, then take a final top-up extra breath so your lungs are replete with oxygen, and then breathe slowly out through your mouth for a count of 7. If you do just a few of these repeatedly, you can really feel the tension leave your body and your heart rate slows.

I also knew that I needed oxygen in my system as the air at nearly 5,000m is very thin, at just 11.2% that is half the oxygen available at sea level. My lungs were really burning and I could only move a short distance before stopping and sucking up more air. I learned through reading the hiking companion, Trek Ladakh, that you should only really look to ascend 500m or so each day, ideally sleeping above your destination point the next day, to allow your body time to acclimatise. What I was trying to do was go from 3,900m to 4,900m in one day, and my body was not happy with me.

Previously while hiking, I’ve noticed the effects of thin air at around 2,500m, and this was the highest I’d ever been and my lungs were burning with the sensation of climbing upwards at this height, but also on a surface that felt like trying to run in soft sand on the beach.

And, so, the physical effects of the altitude were also impairing my thinking. Through the recentering that took place with a series of deep breaths I reminded myself of one of the reasons why I was taking the hike in the first place.

Before the end of the summer term, I felt a “knot” in my stomach and because of my father’s/grandfather’s history of colon cancer, I recently went for an endoscopy and colonoscopy. It was with a slight sense of dread, as, to borrow from the realm of medical jargon, they perform this mildly invasive operation by sticking a camera up your arse.

One thought which struck me quite profoundly was the idea that were the diagnosis severe, this might be the last time I climb this mountain. Or, regardless of that, at 43yrs, at middle age, given my hopes and ambitions to travel to many other places, then, it was more than reasonably likely, that no matter how beautiful this scenery was, that I would never climb this mountain again. It really gave me pause to slow down and appreciate the moment, as well as compel me to carry on.

Writing in The Body Keeps the Score, by Besser van der Kolk, and in Gabor Mate’s book, The Myth of Normal: Illness, Health and Healing in a Toxic Culture, both authors affirm that we are impacted by our psychological profiles in profound ways. Mate criticises Western medicine’s tendency to administer pharmaceuticals to treat the symptoms of our unrest; yet, Mate and van der Kolk both make the case that in this modern world there can often be psychological factors causing physical symptoms.

Luckily, upon my return, I got the all clear, aside from gastritis which could be linked to diet and to stress, though the summer trip to India was highly restorative from a mental and physical viewpoint. And, of course, once you have received some positive news, that also ameliorates the stress that was exacerbating the gut spasm, and so a healthy mental-physical feedback loop is created.

So, eventually, I can let you know that I was able to reroute my path, get to the ridgeline, and then descend down to Stok-La Pass, where I was rewarded with the most sublime view of mountains, valleys and rocky desert that I have ever seen.

Life has a funny way of throwing things in your path, and you need to try to maintain a clear head to make progress through the various obstacles and tests that come your way.

As HT students you have the potential to start to think today about the ways in which you can technologise your body and mind for a healthier and more positive tomorrow.

======================================================================

Follow-up questions for students to write their own personal psychosomatic reflections

- Can you describe a moment when you were “stuck”? This could be a psychological moment, or related to where you’d reached the limits of your physical strength. It need only be a vivid moment, and please make sure it is one you are comfortable sharing. No expectation to share anything too personal.

- What’s an early childhood memory that comes to mind based upon what’s been described? I’d like you to stop to think about it for a moment or two, and see if you can examine how you were thinking and feeling at the time, and why that memory might have been retained by you for so long…

- As you think back to that one particular moment in time, what thoughts were going through your head? Perhaps you only retain the emotional imprint of the moment, rather than vivid details. But try to think back as clearly as you can and see if you can unlock some associations through sensory memory.

- What do you think about this claim: that we experience the world through our minds and bodies? At school we spend so much time focused on developing our cognitive technologies, but those are moments prescribed by the timetable and whatever homework you might have. Much of the world that we experience is through tacit knowledge, that is, time spent as sensory creatures establishing our meaning and position in the world.

- Do you agree? How so if you do? Can you think of moments where your body has given you a message to respond intuitively to a situation? When have you stopped deep cognitive thinking, and embraced being immersed in your own tactile experience of the world?